| 25 September 2020

Sexual Health Nurses are ideally placed to help patients navigate their entire journey when it comes to contraception, family planning, and sexual health and wellbeing. Yet, the story of how nurses came to the forefront of sexual health services is laced with exploitation and perturbation. Such discontent has arguably trickled down to today, with sexual health nursing recruitment and retention facing a ‘succession crisis’ and staff morale at an all-time low. Here, we take a look back at the last 20 years, the debates around issues of exploitation, inequality of pay and perceived competency and interrogate the question: have sexual health nurses been pushed beyond their skillset?

While many of us might think sexual health means reproduction and family planning, there’s so much more to it than that. And at the end of the 1990s, there was a lot to be concerned about.

STIs were rising. Rates of teenage pregnancy were sky-high. And healthcare services were close to becoming totally overwhelmed. What’s more, we’d had the spectre of HIV and AIDs hanging over us for over 20 years.

Such hurdles called for major reform and, whilst we very much take the constant reinvention of NHS policy for granted today, back in 2000, the sexual health role redesign agenda was groundbreaking.

The birth of nurse-led services

In 2001, the Department of Health produced its National Strategy for Sexual Health and HIV – the first-ever such formal document in the UK.

As a ten year plan, the strategy was criticised for its biomedical focus in terms of getting the balance right between a medical and social understanding of sexual health. What made the plans seminal, is that they were the first to recommend some aspects of care to be carried out by appropriately trained nurses, not just doctors.

Clinics were beginning to see that specialist nurse-led services were obtaining equal or superior patient satisfaction to care delivered by doctors – putting it down to either their greater interpersonal skills or the ‘One-Stop-Shop’ model of care they operated within. Others attributed these levels of patient satisfaction with the service to the emphasis nursing puts on patient education and preventative healthcare (Campbell, 2004). These elements remain two very important elements of sexual health as well as potential explanations for why nursing remains one of the most trusted professions today.

While other think tanks produced various policy suggestion documents in the next few years such as the Recommended standards for sexual health services (2005), it wasn’t until the summer of 2008 that the 2001 Sexual Health Strategy was next reviewed. This was mainly thanks to the work of the Independent Advisory Group (IAG) for Sexual Health and HIV. The report acknowledged the positive outcomes of service modernisation.

One key area highlighted was the way the role of the sexual health nurse had developed. As well as family planning and Genitourinary Medicine (GUM) specialists, we now had nurse consultants and nurse practitioners. And nurse-delivered services were key to the whole agenda.

After the 2008 Financial Crash, the Austerity measures brought in by the government affected many aspects of life, including health provision. Two years later, when the Cameron-Clegg Coalition Government came into power, a further review of sexual health provision was delayed.

What’s come of the last decade?

Finally In March 2013, however, another new Framework for Sexual Health Improvement in England was produced. This included a clear call for the expansion of the qualified nurse role, namely staff who are appropriately trained and meet recognised professional body guidelines, such as the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) and the Faculty for Sexual and Reproductive Health Care (FSRH). Curiously, the strategy had remarkably little to say otherwise about how the sexual health clinical workforce should be trained.

The influential Willis Commission in 2012, followed by the seminal Francis report in 2013, also made recommendations for the future of the profession as a whole. The Francis Report investigated several drastic failures of care at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust, many of which tragically resulted in fatalities. The Trust was fined and later decommissioned. The tragic events sent shockwaves through the health community and have had a significant impact on the culture of the NHS, including training.

Professional grey area – role expansion or exploitation?

As the supply of trained doctors choosing to enter the speciality has decreased in recent years, and the need for patient care has increased, professional boundaries between nursing and medicine have continued to blur.

In sexual health, those boundaries have shifted dramatically. Many nurses have developed competencies and skills in areas once considered to be the realm of doctors, such as ultrasound scanning, the insertion of intrauterine devices (IUD/Coils) and implants, and delivering HIV test results. Some aspects of sexual health nursing support have remained constant for decades, including STIs, pregnancy, and contraceptive advice, while other areas have developed more recently, such as LGBT+ sexuality, including supporting those who are transgender.

Free training on the job, enhancing your duties, expanding your repertoire…what more could you want, right? Isn’t that what everybody is looking for in their career?

On paper perhaps; however modernisation does not always take the most innovative or fair course. We know this to be the case in society as a whole, whenever modernisation or change takes place – take the pedestrianisation of an inner-city road; one person’s ease of life will be to another’s detriment. The pedestrianisation may be beneficial for those who walk into town but cause delays and diversions for car drivers.

So whilst some, at times, argued that the opportunity to advance the nurse’s role should be viewed as a positive career development that would enhance future recruitment and retention within the speciality, the reality for many was quite the opposite. This is still evident today.

What came to light is that when nurses were called upon in times of crisis to fill the skills gap, this often inevitably resulted in a lack of choices in the way or direction their roles actually developed. Any further discourse on this modernisation – a change agenda that has become externally driven – is frequently used to covertly restyle people’s jobs and pay them less. (We’ve probably all heard of scope creep, if not experienced it personally.)

The lived experience

Tensions and conflicts inevitably arise during organisational change – were nurses just bargain-basement doctors, cheap at half the cost or less of a doctor? Were they being manipulated into extending their roles prematurely?

In addition to feelings of being ‘pushed’ and ‘pressurised’, 10 sexual health nurses interviewed in a 2014 study reported feelings of isolation and a lack of support in the development of nurse-led services. Several cited issues of exploitation and a perception that they are a ‘cheaper option’ to fill the skills gap, whilst others expressed anxieties that they were not “clever enough” (in comparison to doctors) to fulfil certain added responsibilities (in this case, non-medical prescribing). Unsurprisingly, issues around morale were found in what could be described as “the difficulties of finding time to care within a changing role”.

Whilst sexual health nurses were clearly developing their clinical skills and knowledge, not all embraced the changes: overwhelmed by the added responsibilities and power imbalances within doctor-nurse relationships. This disruption to their figured world of nursing did raise issues for the future of the industry but arguably sudden change and imbalance always takes some getting used to.

Where are we nearly a decade later? Have those imbalances levelled out? Is it a fairer playing field? Is workforce recruitment and retention higher? Do nurses have a stronger sense of self, both independently and in relation to doctors?

Where are we now?

So what challenges face the sexual health sector currently?

Attendances at sexual health clinics have increased by 13% between 2014 and 2018, but at the same time, demand has increased.

Other concerns, highlighted in several reports, include the provision of abortion services, many of which are provided outside the NHS, as well as integrated care and public health services in local authorities.

There is also some difficulty around collecting data on the sexual health sector. Mainly because sexual health, reproductive health, and HIV workforce have never been clearly defined, despite nurse-led clinics remaining a vital first point of contact for many patients and service users. Thus, sexual and reproductive health (SRH) consultants may be miscoded as genitourinary specialists, for instance, while a non-sexual health consultant may be coded as sexual health solely because they hold a weekly speciality clinic in this area.

Typically, clinicians specialise in either Genitourinary Medicine (GUM) or Community Sexual and Reproductive Health. In these areas, the non-medical staff are usually nurses or midwives, healthcare scientists, sexual health advisers, allied health professionals, administrative and clerical staff. The role of the physician’s assistant is also starting to become more common in this speciality.

One of the major issues in this speciality is that many sexual health professionals feel they lack parity with other parts of the NHS. Morale is extremely low; there are high levels of staff sickness, and complaints and reports of incidents have risen dramatically.

Recruitment and Retention

We know, to minimise the effects of fragmentation, and to provide a safe, consistent, responsive service, it’s essential to have a constant and sustainable flow of well-trained staff.

According to The British Association of Sexual Health and HIV, sexual health staff morale is at “breaking point”, with 81% of members reporting a decrease in staff morale from 2017 to 2018 and 49% reporting it had done so greatly.

If you know anything about the NHS you’ll be unsurprised by the factors this is attributed to. The organisational change, funding cuts, heavy demand, and service closures intrinsic to this period of austerity have put pressure on staff across the service, especially sexual health.

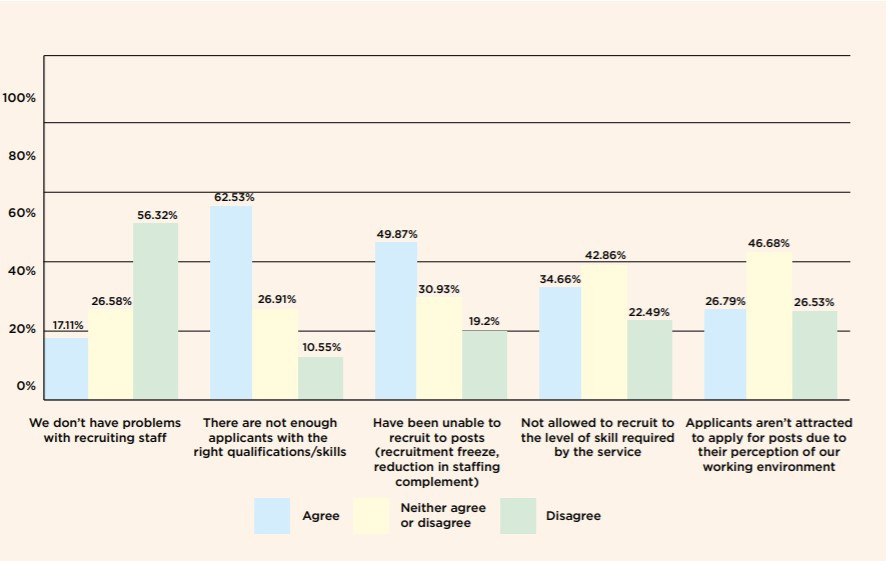

Uncertainties and pressures in the sector have inevitably made working in sexual health less attractive to both new and existing staff, making recruitment and retention an uphill battle (see below image). That’s quite apart from the fact that many existing staff members are ageing, and leaving – it’s estimated that one-third of the workforce could retire by 2023 (in 5 years).

With staff not being trained in the skills required to replace the leavers, and the status of GUM going from a very competitive specialisation to one of the least popular with clinicians, the sector is evidently facing a “succession crisis”. In 2018, less than 40% of training posts advertised were filled, due to a simple lack of applications.

Source: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmhealth/1419/report-files/141909.htm Figure 5: applications to GUM training posts have decreased, based on data from the Specialist Advisory Committee for Genitourinary Medicine

In a 2018 RCN Survey into sexual health and the role of nurses, recruitment freezes/blocks were given as reasons for lack of adequate staff recruitment in over 83% of cases. The respondents also indicated concern that the service is just not seen as attractive to new staff.

The fact that more than half of respondents (62.5%) stated there was not enough staff with the right skills sheds light on an even bigger problem facing the role, training (or lack thereof it).

The importance of training

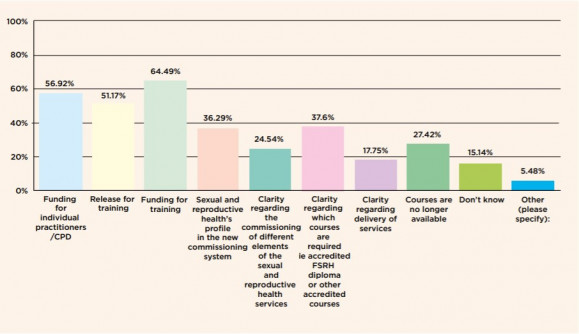

Retention and recruitment difficulties are exacerbated by diminished training opportunities, namely, limited learning and development opportunities which thereby feed into the decreasing attractiveness of working in sexual health.

“Training across multi-disciplinary teams is vital, but training is falling through the gaps. We heard that although services would like to build capacity and develop the clinical and wider workforce, they are not incentivised to invest in training.”

Nurses without the knowledge and skills are often unable to get employment and unable to fund courses themselves to gain the transferable knowledge and skills required. Funding for courses and problems with being released from work for training were cited as issues for the majority of respondents. When asked how easy it has been to access appropriate and accredited post-registration sexual and reproductive health qualification, 63% of respondents stated that being able to devote time to their study was their concern.

There is one particular aspect of the current healthcare system that sexual health services suffer the implications of significantly and that is the commissioning arrangements in the wake of the Health and Social Care Act 2012. The local authority commissioning and competitive tendering has arguably exacerbated issues around training more than anything. Because training is not included in service specifications, when an organisation wins a contract to provide a service, they are at liberty to essentially ‘opt-out’ of participating in training programmes. The Interim NHS People Plan, sometimes referred to as the Harding Review, provides a framework for the development of the workforce plan to go alongside the NHS Long Term Plan. It has laid out approaches to help tackle this particular issue.

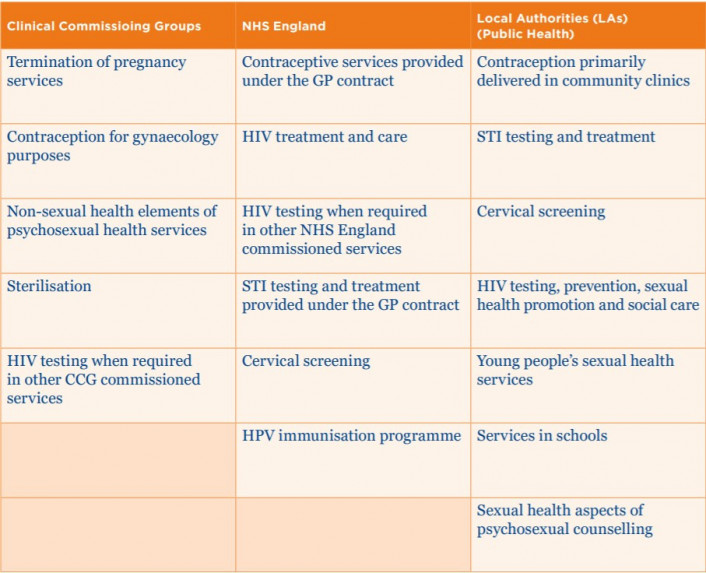

What’s more, nurses report that commissioners overall disregard the importance of contraception care and sexual and reproductive health to the wider system. Table 1 below, shows how different elements of sexual health are commissioned in England. This fragmented system has invariably led to confusion and variation in provision, for example, in some areas women will be offered contraception as part of the termination of pregnancy and in others, they won’t (despite Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RCOG) guidance (2011) recommending it). Not only does this deplete access to services, all the while increasing health inequalities, but it also confuses training for staff.

In response to such concerns, the Nursing and Midwifery Council ratified their training standards to incorporate sexual health as part of the core element of health promotion (2018). The RCN also researched the impact of service and funding changes in England, highlighting the fact that many universities do not have teaching staff with the requisite skills to teach sexual health.

Where Are We Going From Here?

Dual-purpose training for doctors and nursing staff has already been highlighted as a likely development in the near future. Not only will this approach allow clinical staff to gain a wider range of skills, but it will also help to provide a more flexible workforce. Since, in general, Health Care Support Workers (HCSWs) are also likely to play an increasingly important part in the interprofessional sexual health team. They may be called upon more frequently to carry out relatively straightforward, routine tasks like pregnancy testing, or screening for Chlamydia.

One major change on the horizon is that there will be a new dual-accreditation for GUM and General Internal Medicine (GIM) physicians. This is following the 2015 Shape of Training review which suggests options for potential restructures of postgraduate medical education and training in the UK. Combining the qualifications will hopefully make the training more attractive to new applicants.

Meanwhile, nurses may well find themselves working in areas which have previously been regarded as somewhat niche, including psychosexual counselling, or HIV care. To try to redress the lack of clarity around current career pathways, the RCN has produced a short guide to the options available.

We suspect outreach will become more common too. In the wake of COVID-19, at least some will be online, via Skype, WhatsApp, Zoom, or some other mysterious package we haven’t yet met.

In Conclusion

So what conclusions can we draw from the current body of research in this area? The demands on sexual health services continue to grow, at the same time as many clinicians are less likely to opt to work in the speciality. It’s apparent from the publications of the BMA, HEE, NMC, RCN, and others that there aren’t currently enough appropriately trained staff to support the needs of the service users. And it’s also fairly obvious that the demographics of the workforce mean that succession planning is going to be extremely difficult, as many experienced staff members leave and will not or cannot be replaced.

One key message is that there will increasingly be a need for doctors who can work across broader specialities in different settings. Nurses, allied health professionals, and support workers are almost certainly going to have to be upskilled. (Whether they’ll receive appropriate compensation and remuneration for that increased level of skill remains debatable.) And even doctors are likely to have to take on two areas of expertise rather than one (namely, GUM and internal medicine).

Not only is there a lack of qualified staff, but there’s also a lack of qualified nurse trainers to deliver those skills – so educators too are likely to find themselves having to gain new skill sets and knowledge. And since providing sexual health support is part of the larger health care landscape, the effect of the Francis Report on the training of clinicians will continue to make itself felt.

So you know that saying, you learn something new every day? It’s especially true when you’re a member of staff in the ever-changing sexual health speciality.

eLearning for healthcare

Unlock your potential – our healthcare eLearning courses make it simple to access high quality content, that deliver on your statutory and mandatory training and compliance needs.